New ECF cycle infrastructure factsheet: interruptions and delays

ECF has released a new factsheet that compiles, compares and analyses requirements for avoiding interruptions and delays across cycling standards and guidelines from five countries.

The European Cyclists’ Federation (ECF) has published a new factsheet on interruptions and delays on cycle routes. The report is a meta-analysis of requirements and recommendations from five different European countries with a diverse range of climates, levels of cycle use, population densities and topographies. Its recommendations contribute to the ongoing discussions at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe level on quality requirements for cycle infrastructure.

Why are interruptions important?

On a typical bicycle, cycling stably without excessive effort requires maintaining a speed of 15 km/h or higher. The need to slow down below this speed or stop altogether and put the feet on the ground is an inconvenience and reduces the efficiency and competitiveness of a cycle trip. It takes time and wastes energy. Up to 85% of the time lost by a cyclist in a built-up area is caused by traffic lights. A single stop consumes as much energy as cycling an additional 75-100 m. Frequent stops and/ or long waits reduce the credibility and usability of dedicated cycling infrastructure.

Interruptions are also a safety hazard. A cyclist losing balance while slowing down or completely stopping to give right of way to another road user is one of the typical scenarios of single-vehicle crashes, especially for older cyclists.

How to quantify this aspect of the quality of cycle routes?

Many standards and guidelines note the need to minimise stopping and delays but do not provide any specific thresholds or metrics that would allow comparing different route variants or solutions. Nevertheless, across the selected documents from five countries, we managed to identify two recurring parameters: number of interruptions per kilometre and time loss per kilometre.

Interruptions include the need to yield to other traffic, traffic lights and other situations that might require a full stop, for example, because of a railway level crossing, a moveable bridge or the need to use a lift to continue the journey along the route.

Times loss considers both the probability of stopping and the average waiting time in case of a stop. For example, if cyclists have 12 seconds of green light in a 60-second traffic light cycle, it translates to an expected delay of 19.2 s when crossing.

“Green wave” synchronised for 20 km/h reduces the time lost at traffic lights for cyclists

Recommendations

Main cycle routes should be planned to minimise the number of intersections requiring stopping or giving right of way. If a stop is necessary, then the maximum and average waiting time should be minimised.

Following the meta-analysis of available guidelines and standards, ECF formulated recommendations vary the maximum number of interruptions and delays per kilometre depending on the category of the cycle route. Per kilometre of a basic cycle route, up to 1.5 stops and 40 s delay are acceptable. For a main cycle route, these values should be reduced to 1 stop/km and 20 seconds/km; for a cycle highway, they should be reduced to 0.4 stops/km and 15 seconds/km.

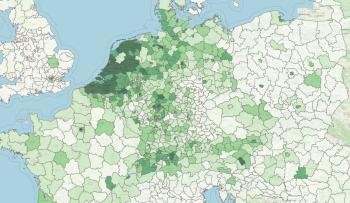

Comparison of signalised and non-signalised intersections in two parallel corridors in Brussels: Chaussée de Louvain (distributor road) and F203 cycle highway. (Background credit: OpenStreetMap.)

Minimalising interruptions and delays, especially in urban areas, is mostly decided in the planning stage by choosing the right itineraries for main cycle routes. Depending on the local context, the optimal corridor may be the following:

- Local streets: local streets have less need for traffic lights than distributor roads. They can be arranged in a way that gives priority to intersections to cycle traffic moving along a selected corridor; while making it impossible to use the same corridor through motorised traffic.

- A railway line: there is usually a limited number of roads crossing the line, and the main roads usually cross the railways by bridge or tunnel, making it easy to provide a grade-separated solution for cyclists. Many Belgian cycle highways follow rail lines, for example, F1 between Mechelen and Antwerp.

- A river or a canal – as with railway lines, the number of crossings is limited, and in many cases, their design facilitates grade-separated solutions for cyclists.

- A primary (trunk) road with a very limited number of intersections. The section of the cycle highway F203 entering Brussels is a good example of such an approach.

Regardless of the corridor chosen, on crossings with local roads, the right of way for the cycle route should be established. On intersections with main roads, grade-separated crossings are preferable.

Download the report

You can download the full report here.

Regions:

Contact the author

Recent news!

Contact Us

Avenue des Arts, 7-8

Postal address: Rue de la Charité, 22

1210 Brussels, Belgium